Finally, the long-dreaded and much abhorred Biology paper was completed about 6 hours ago. The two hours of answering multiple choice questions made me realize a couple of things. One, that glossaries and indexes are grossly underrated. Two, that 'pseudopod', a term I first came across when introduced to horror fiction podcast, has its roots in biology. This, of course, turned me off for the briefest moment but not before surprising me so much that I chuckled to myself, desk #166, in a hall of 800 students. Biology - I sit here with my small glass of low fat milk and I toast to you: never again, never again. Anyway, I've recently been hooked on to an audiobook titled "How to Disappear Completely" by Myke Bartlett. Ignore the obvious pop culture reference in the title (I'm not sure if it was intended but English band Radiohead produced a song with the same title in their Kid A album) because this book, aside from being set in the same country, has nothing to do with it. Ignore, also, the promotional cover (left) because there are good reasons to listen to the reading of this book.

Anyway, I've recently been hooked on to an audiobook titled "How to Disappear Completely" by Myke Bartlett. Ignore the obvious pop culture reference in the title (I'm not sure if it was intended but English band Radiohead produced a song with the same title in their Kid A album) because this book, aside from being set in the same country, has nothing to do with it. Ignore, also, the promotional cover (left) because there are good reasons to listen to the reading of this book.

I'm only at my fourth chapter now so if the rest of the book turns out to be crap, you can't blame me. I will, however, state my intentions for posting this: Kilbey Salmon and London. Now, I know that this is a work of fiction and that, by default, makes Kilbey (a character of Bartlett's) fictional as well. But you really have to hear Bartlett's voice. Oooh, he sounds like honey melting slowly over the surface of smooth things, he glides and trickles like rich golden drops of goodness. And Kilbey's smooth badboy ruffian character (etched out pretty nicely, actually - well in Chapter 3, anyway) together with this impeccable reading voice has close to done me in. Not to forget, I've a strong predisposition for London settings - the griminess of the city, its expanse and coldness, dirty alleys and danger, junkie fixes and drug dealers and decadence; the architecture and shiny beautiful buildings and the stories behind every stranger's every look. These aren't terribly good reasons, I know, but there's something about the city.. an alluring mix of romanticism juxtaposed with harsh reality that one rarely comes across. Yes, I've an extremely soft spot for London. That being said, I really don't know if I'm hooked onto this podiobook because it's well-written although a case can be made for that - it certainly is gripping, it moves at a good pace, I suppose (only because I'm no expert on this) fans of the thriller/suspense genre would appreciate it - but more than anything else, I am enjoying Kilbey's oozing-with-sex personality/voice and the London setting; all extras are a bonus.

How to Disappear Completely by Myke Bartlett @ Podiobooks.com

Monday, April 30

Podcast: How to Disappear Completely

Sunday, April 29

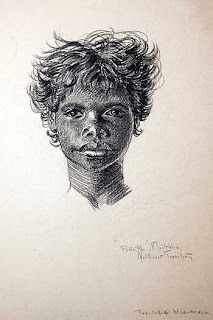

Peter Pan

Caroline Mytinger's sketch of Peter Pan is the closest web source I could find to my idea of him - ruffled curly hair and eyes full of kisses stolen from Mrs Darling's lips.

What a lovely, lovely story. How I long to be one of the Darling children (and I think we all do) and take flight from this reality.

As a character, Peter resists definition. One can only point out the discrepancies in his personality. Peter is innocent, yes; he doesn't understand or know that Tink, Wendy and Tiger Lily want romantic love from him. This idea, it appears, of romance, is completely lost on Peter. Perhaps it is inaccurate to say he is ignorant or does not understand; the sense one gets is that such an idea does not even exist to Peter, that is he above and beyond concepts that hint at any definite morality (the assumption is that Peter is innocent because he does not understand like, love, or attraction, and by implication, does not understand sex nor the need for it, which, therefore makes him innocent, i.e. GOOD). In the final chapter, upon realizing that Wendy has grown up, he cries - I think - not because of unrequited love or any of that mainland rubbish but because the sublime experience of childhood, the time of flight of imagination (both literal and otherwise), has passed for Wendy, and he mourns this loss on her behalf. Yet, despite this innocence (see parenthesis above), Peter kills swiftly and, just as easily, 'forgets them after'. Wendy is aghast at this and tries to make him stop. She does this by inventing a game where he does nothing all day except sit on his stool and go for walks to improve his health, but he soon gets bored. He is youth and joy, the embodiment of a Platonic child with strange mixes of mischief, purity and amorality.

Friday, April 27

snacks and short stories

The weather recently has been terribly unpredictable. Shaz calls it schizophrenic and in doing so, reminded me of my initial one-sided disagreement with it early on in the year. It bothered me that every time I went out, I wouldn't know if it was going to rain or shine - but that's just the magic of it. Out of the blue, a distant a rumble, then an overcast sky and the heavens open to pour out this wonderful, gloomy weather. Just perfect for a shadowy room and light from a single lamp. And a book. And crackers.

My father bought me Jacob's Cream Onion crackers this morning while I was at school. The fridge is chock full with Magnum ice-cream and chocolate bars (Crunchie, my favourite!).

A few weeks ago, I was looking through the bookshop on campus and saw this title: "The Best Short Stories of Fyodor Dostoevsky"; these include 'Notes from the Underground', which I've been desperate to lay my hands on ever since I was introduced to the Russian author. For several weeks, I flirted with the idea of buying the text (I'm an extremely indecisive buyer. One minute, I'd have made up my mind to get it - "I must, I absolutely totally must!" - and then - "Maybe I can guilt trip Anil into getting it for me.." or "Maybe I should go to the library instead" - and I vacillate fiercely between these two opposites), and again today, when I went to buy Cranberry juice and 'accidentally' detoured to the literature section. I picked it up, suppressed any other thought, and now I am sitting with it in my bedroom while the rain pours outside. I would like to say that I will resist the urge to read it before my exams end on the 3 May, but alas, I have no such discipline.

Stainslaw Lem's Solaris was available as well - it was the last copy - but there was a grumpy lady who made such a scene about the pages being weathered and yellow (and she was standing next to me, enquiring about another book which I presume she complained just as much about) that I left without purchasing it. Well, good thing too. The universe is insisting that I budget. Until then, I can only dream:

Stainslaw Lem - Solaris

Tolstoy - War and Peace

John Barth - Chimera

Dostoevsky - The Idiot

H.P. Lovecraft - Collection of Stories

Frank Herbert -Dune series (this I'll probably get from the library)

..and several others. I have three months; that's a pretty long time to a college student.

Tuesday, April 24

Hofmannsthal's evening ballad

Sunday, I discovered a gem laying in wait in my paper tray (yes, I am a student with a paper tray; it allows me to collect all my mess and junk in a specific, neat corner only to (ironically) make space for more book clutter on the desk). It was a poem by Hugo Von Hofsmannthal titled Ballade Des Ausseren Lebens (translated: Ballad of Outer Life), followed by a translation and a paragraph on the poetic use of the word "evening", written by A.O. Jaszi . The book is called "The Poem Itself," edited by Burnshaw, in the Penguin collection (1960).

(1) And the children grow up with deep eyes (2) Who know of nothing, grow up and die, (3) And all people go their ways. (4) And the bitter fruits become sweet (5) And fall down at night like dead birds (6) And lie a few days and spoil. (7) And always the wind blows, and again and again (8) We hear and speak many words (9) And feel [the] pleasure and weariness of our limbs. (10) And streets run through the grass, and places (11) Are here and there, full of torches, trees, ponds, (12) And menacing ones and death-like withered ones... (13) Why are these raised up? and resemble (14) Each other never? and are countlessly many? (15) Why do laughing, crying, and turning pale alternate? (16) Of what use is all this to us and all these games (17) Who are (after all) great and eternally lonely (18) And, wandering, never seek any goals? (19) Of what use is it to have seen so many such things? (20) And nevertheless he says much who says "evening", (21) A word from which deep meaning and sadness run (22) Like heavy honey from the hollow comb.

Jaszi continues below on the poet's use of the word "evening", the use of which brings beauty and unity to the poem.

The word "evening" is a container-word - not of denotation but of emotion, of emotion composed of all the feelings, of depth and sadness and sweetness; of the emotion transcendent. To say "evening" therefore means to write poetry...Hofmannsthal's ballad can be called dreary and decadent only if the words that compose it are understood as being carriers of a life content. But when the words are understood poetically, they convey quite a different meaning. Every word here, every and, every dead bird, every tiredness of limb, must be read as a poetic word...As such it is a bearer of poetic delight - of depth, sadness, sweetness. Every word in this ballad is poetry, for every word says "evening", or, to quote St. John of the Cross, is full of "the knowledge of the evening."

Whether our knowledge of the poetic evening contributes to this or vice versa is hard to say.. perhaps it is a constant exchange that bears no fruit in either. Like a juicy peach that must be consumed immediately without thinking of its passage into your hands even while subconsciously appreciating (and thanking) the journey without which consumption would not have been possible. I read this poem and the exposition on the use of "evening" at night (as it were, most of my studying takes place post-sundown), and it turned out to be a very apt time for it seemed my senses were heightened and my appreciation for the poem came not intellectually but emotionally.

Saturday, April 21

Podcast: Alice In Wonderland

Last night, whilst reading under a bright table lamp and in between midnight smoke breaks and short bursts of conversation on MSN, Jamila introduced me to the wonderful world of podcasting. Prior to last night, I was only mildly interested - that is to say, interested only enough to know something about it without doing anything about it - but in the span of a few decisive minutes, a transformation took place and I became a podcast lover. Podcasts are an amazing new trajectory in literature. Jammi said, interestingly, that the wonder of podcasting lies in the idea of storytelling reverting back to its original form. I cannot agree with her more; before print and mass production, there were voices and memory. Stories, then, were fluid and fluxing, (and even some poetry begs to be read aloud to be best appreciated; unfortunately, this is lost on most people; the aural aesthetics of Gerard Manley Hopkins' poetry is one such example; I recommend reading "As Kingfishers Catch Fire") and emotions expressed not silently in our heads as we read now with our mind-voice but tangibly and audibly, passing down from mouth to mouth, voice to voice, until finally being immortalized in print.

And if you go chasing rabbits

And if you go chasing rabbitsAnd you know you're going to fall

Tell 'em a hookah smoking caterpillar

Has given you the call

- Jefferson Airplane, White Rabbit

Alice In Wonderland is indisputably one of my all-time favourite stories. What an acid trip it is! A delight to read and an even greater delight to listen to. Natasha Lee Lewis does a wonderful job of reading the story - one chapter a month, and by the time she's done, "everyone will be a year older".

Podcast here.

And if you want to read along (because that's how you like to roll), there's an online text at The Online Literature Library.

Friday, April 20

The Art of Crime and Punishment

If only he could have grasped all the difficulties of his situation, its whole desperation, its hideousness and absurdity, and understood how many obstacles and, perhaps, crimes he might have to overcome and commit in order to get out of there and get back home, it is quite possible that he would have left it all and turned himself in, and this not even out of fear for himself, but solely out of horror and revulsion for what he had done.

- Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

What is the genius of Crime and Punishment? Undoubtedly, it bends well to produce results to the conventional literary tools of criticism: there is irony, satire, individualization, social theory. All of these make a book great, given, of course, that it is, above all, well-written. But the art of Crime and Punishment goes above and beyond that. It is a feeling one gets when reading the novel, of fear, of obsession, of truth, that has been novelized so explicitly yet sublimely that it is difficult to stop and say about any emotion, "Here, right here is the genius". It is beyond realizing the extent of Dostoevsky's imagination, for how do you call what is real and penetrable the work of imagination? Imagination should be a thing of fancy and lofty idea(l)s, like a house of cards made of clouds; it is fantasy. But Dostoevsky does not imagine - he merely captures the purity of emotion and translates it into the fiction of a young former student, Raskolnikov. That is the sense I get no matter how many times I read Crime and Punishment; how can Raskolnikov be an evil man? His psychology has been traced at every step and turn of thought, and articulated with such precision that he appears normal. He is normal, apart from experiencing an intensity of emotions that are, presumably, the results of suppressed guilt and dividing opposites.

And there is something almost fantastical and surreal about Sonya's love for him. The harlot serves as an instrument for divinity, the pure harlot redeems an anguished convict. There is little more one can say about this strange but perfect relationship without delving into technicalities which automatically ruin the sublimity and pathos that comes out of every meeting between these two. I have asked myself this question many times: why Sonya, what about her? and I suppose (because I cannot be sure, such is the vacillation that this text inspired in me) it is her impossibly beautiful character, her ultimate goodness, her purely instinctive sacrifice, her quiet, shy yet knowing demeanor, pale skin and big eyes, her abject poverty. It is a beautiful mix.

Thursday, April 19

Have you ever felt so overwhelmingly sleepy or tired that your eyes glaze over words, blur them into continuous sentences; your body refuses to move even when your mind knows and understands inertia; speaking is a chore, a great skill, an eloquence that might, just might, return after rest? Yet Dostoevsky remains before you as ever before, the page ears outline numerous bent-into triangles and Marmeladov says drunkenly and despairingly, "And what if there is no one else, if there is nowhere else to go! It is necessary that every man have at least somewhere to go. For there are times when one absolutely must go at least somewhere!" and there is a prostitute with a pure soul who falls in love and devotion with a tormented murderer.

Life, all of life, in a jumble of words.